轉載自 Blog Camp in F/T, 25/11/2012

By Amanda Waddell

Two productions in particular in the F/T Emerging Artists Program, “permanent value” and “American Dream Factory”, boldly chose to confront capitalism and the commoditization of humanity as an overriding theme.

First, I’d like to look at how the structure of the first half of “permanent value” approached this, and then how “American Dream Factory” created a tableau of images and short scenes that played with the idea of domineering American culture and the degradation of human value brought about by industrialization and globalization.

What first intrigued me about syudan:hokoukuren’s production “permanent value” was the premise of the first half of the production. Audience members were refunded 500 yen from their initial ticket price in exchange for the chance to “direct” one of the actors. At first, the audience was strapped for ideas, which considerably slowed down the pace of the performance. However, the long unsettling silences were by no means the fault of the troupe, which even provided a “sample menu” of orders and directions to chose from, but rather the uncertainty of an audience that was suddenly given direct monetary power over the actor onstage. But once audience members became more familiar and comfortable with the process, people began to raise their hands and pay for the chance to order the actor around. While the lone actor onstage struggled to meet everyone’s demands (from perform the scene quietly, climb a ladder, perform outside the theater, etc.), other performers also joined in, claiming that they could satisfy the audiences’ needs better.

The performance was less of a comment on the whole capitalist system as a direct example of the commoditization of art and entertainment. Although as audience members we weren’t allowed to determine how much the actor’s efforts were worth, like a street performer, the audience was exposed to the bare bones transaction of entertainment for money. In this capitalistic nightmare, the joy of creating art is replaced with the desperate attempt to earn as much money as possible, no matter how small. Also, like a street performer, the actors all carried their earnings in a cup.

In the second half of the show, using the money they had earned from their efforts in the first half, the actors began to order each other around, dropping a coin in their respective cups. The continual sound of coins clinking in the glass was a constant reminder that this world is one that is built on money. Everything’s value is determined by how much you are willing to pay for pleasure and entertainment.

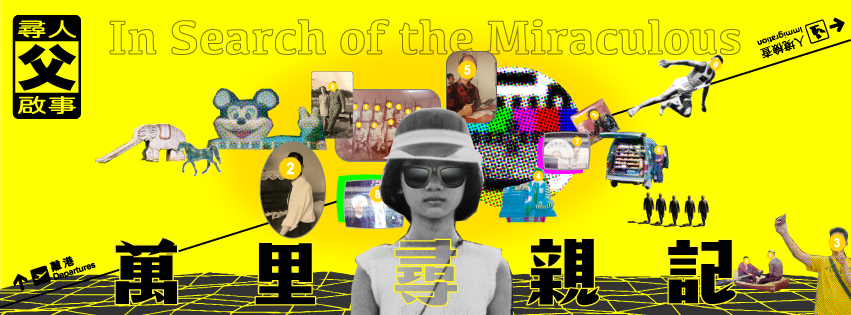

Against Again Troupe’s “American Dream Factory” is a nightmarish world of images and short scenes saturated with American culture and iconography. This all-encompassing hijacking of Taiwanese culture is the result of American imperialism spreading around the world via capitalism. The performance did occasionally drag, but nonetheless, there were powerful scenes with interludes in the life of fast food chain McDonald’s mascot character, Ronald McDonald. By depicting his rather humble daily routine, the audience was able to relate to him as another human trapped in the everyday hustle and bustle.

Ironically, this Ronald was also a fan of Mickey Mouse and religiously watched a Mickey Mouse cartoon every morning, not to mention owning a pair of matching Mickey Mouse slippers. An American icon like Ronald McDonald consuming another American icon’s merchandise depicts a grotesquely self-contained capitalist society that claims to fulfill your every need.

Towards the end of the performance, Ronald came home from work and sat down at the dinner table with a takeaway from his fast food restaurant. As he watched a program on the industrialization of America, he started choke down the burger. However being unable to stomach the filth, he continually regurgitated his food, which then drives him to the brink of insanity. These images along with others suggest the inability to escape American cultural dominance and a world that turns everything into a commodity. As an American I was able to sympathize with the bombardment and inescapability of capitalism. Everything has a price.

In regards to the language barrier, the performance was held in Chinese with Japanese surtitles. An English translation of the script was also available at the front desk. However, since the production was predominantly composed of images and short vignettes, dialogue between characters appeared to play a secondary role to the images presented onstage. For example, in one scene a department store customer berates a young saleswoman for selling condoms in a public space. When another young woman comes to her rescue and chases the irate male customer away, the two blow up a condom like a balloon and play air volleyball. Without necessarily understanding every word, these short scenes were powerful enough on their own due to the strong imagery the viewer was left to decipher. In short, “American Dream Factory” was a perfect example of a performance’s potential to be universally accessible with or without surtitles through imagery.